Racomitrium in West Wales

Racomitrium obtusum, for the most part, on a mossy rock near Goginan, CeredigionIf you walk across any of the moorland in Ceredigion, northern Carmarthenshire or northern Pembrokeshire, sooner or later you’ll come across moss-covered rocks. There’s usually a good selection of common mosses and liverworts but one genus in particular can be troublesome to name with confidence and this is Racomitrium which forms large spreading patches as well as smaller cushions on rock surfaces, particularly where the rock chemistry is acidic – hence its prevalence in much of West Wales. And several species can be really abundant.

It’s not helped by the close similarity of many of them, their great variability in appearance and their predilection for growing in very close proximity, often resulting in what appears to be a single patch being a mixture of 2 or 3 species of Racomitrium plus other superficially similar mosses such as Grimmia trichophylla.

Even if you’re an experienced bryologist things are about to get harder as R. obtusum is to be officially designated as a British and Irish species and it can be very common. It occurs with and without awns (hair points). It used to be lumped in with R. heterostichum but that species is now considered to be always awned. R. obtusum was ‘sorted out’, by Frisvoll, back in 1978 so we’ve been a bit slow accepting it in this country but it’s by no means straightforward and the genus is full of backwaters taxonomically speaking. The current situation is that muticous (lacking a hair point) forms of R. obtusum are going to be almost always identifiable but some awned forms will not be separable by morphology from R. heterostichum, at least not with certainty.

In this article, we’re sticking with Racomitrium as the genus name, as will be the case in the forthcoming Checklist and Census Catalogue. Various accounts are available online and the new addition can be found by searching for Racomitrium obtusum or Bucklandiella obtusa. It is in Section Laevifolia of the genus. The controversy on the taxonomy of this complex group is likely to continue however.

Racomitrium heterostichum (lower, left) and R. sudeticum (upper) on a rock on Banc Trawsnant, Ceredigion.

It’s usually possible to spot Racomitrium by its branched appearance (sometimes they’re just closely spaced stems), the frequent presence of hair-points (awns) and by the fact that it’s not Grimmia trichophylla! This last plant is a particular problem because it shares the same habitat and also forms large cushions, sometimes spreading like a Racomitrium. When dry however, it has a peculiar wavy appearance to the leaf which is not shared by any of the common species of Racomitrium and can thus often be eliminated in the field, at least on dry days.

One species, R. lanuginosum, is particularly common and is easily told by its very hoary appearance and toothed hair point. It’s one of the few mosses that higher-plant botanists like to give a definite name to.

Careful surveying of three areas of moorland in Ceredigion has shown that the commonest species on boulders on open moorland are R. obtusum, R. affine, R. fasciculare, R. sudeticum and R. heterostichum. The order of these varies from place to place and whereas in one site there may be a huge amount of R. obtusum, in another it can be mostly R. fasciculare. In more sheltered locations, R. affine is often by far the commonest and R. sudeticum seems to need more open habitats where it can be on every boulder in favoured sites. R. heterostichum is sometimes the least common but then a whole rock face is found where it dominates. So it’s difficult to predict what will be found. R. aquaticum tends to occur in more predictable places where it’s a bit damper – either near water or on north-facing slopes. R. aciculare likes it wet of course but is sometimes found in surprising places such as on tarmac.

Racomitrium obtusum. Note the yellowish tinge which is usually absent in R. heterostichum but this patch is in any case muticous so more likely to be confused with R. fasciculare which has longer narrower leaf apices that tend to stick together when moist. The loose patches, but more especially the long setae, preclude R. sudeticum and the colour is very unlikely for R. affine which is normally at least shortly awned. The plant is nowhere near dark enough nor the leaves stiff enough for R. aquaticum which is also mostly unbranched. The shortly cylindrical, sometimes obovate capsules are typical of R. obtusum.

Racomitrium aquaticum on the shady side of a large boulder. It is often almost unbranched which gives it a different look to most of the other common Racomitrium. It looks hard to confuse with R. obtusum but of course both species are variable.

Field characters of Racomitrium in West Wales

The genus is certainly difficult but not impossible. Much can be done in the field.

R. ericoides. Leaves pale to mid-green, opaque, densely papillose. On gravel or soil and often abundant on forestry tracks. Awns short or completely absent (when it may be mistaken for other mosses). Awns not reflexing when dry.

R. elongatum. Differs from R. ericoides in the longer awns which run down the lamina margins and are reflexed when dry as a consequence..

R. lanuginosum. Not confined to rock and may even be found in bogs. Hoary appearance due to long white awns which are easily seen to be toothed (hand-lens). R. heterostichum can be nearly as hoary in open habitats.

R. fasciculare. Leaves long and narrow in the upper half, without awns and tending to stick together when wet. Sometimes more frequent near streams than on drier rocks on moorland where R. obtusum may predominate. The ‘leaves in short bunches’ character often quoted in text books could lead to confusion with R. obtusum which can sometimes have similar branching.

R. affine. Frequently quite dark in colour but may be lighter green too. Usually at least shortly awned and the leaves are often secund. Most prevalent in sheltered sites such as rock outcrops in woodland but commonly mixed in with other species on rocks on boulders too. This is a troublesome one as it’s not really possible to identify it without taking a leaf section.

R. obtusum. Usually a yellowish green but sometimes duller as in the first photo above. Leaves not tending to stick together when wet. Often lacking awns completely but plants with varying percentages of awned leaves also common. Completely awned forms may be uncommon but appear to retain the yellowish tinge and may have less flexuose awns than R. heterostichum. When fruiting, the capsules are usually slightly wider in the upper half or else shortly cylindrical and certainly worth collecting a sample to check the exothecial cells (see later).

R. heterostichum. Mid- to dark-green, even blackish (but so can be R. affine); usually without a yellowish tinge. Awns always present (beware broken leaf lips), often long and very flexuose when dry. The white awns often contrast sharply with the darker leaves. When fruiting, the capsules are long and narrow, cylindrical. Also essential to collect a sample for checking.

R. sudeticum. Short leaves forming cushions, sometimes quite dense. Usually a mixture of muticous and very shortly awned leaves which are both narrow and clearly V-shaped in their upper half. When fruiting (only occasionally), the short setae and short capsules are very distinctive. Although the short hair points, when present, do reflex in the dry state, this character is often found in other species so needs to be used with caution.

R. aquaticum. A dark plant, hardly branched with stiff leaves which may be erect or secund (curved downwards).

R. aciculare. Leaf apex broadly rounded and toothed but may be narrower. Whole plant usually very dark. May occur on tarmac and rocks in paths as well as commonly on rocks in and by streams. Often fruiting.

R. macounii. Spreading, reddish patches. Leaves with very short awns. Very rare on large slabs of rock in rivers.

R. ellipticum. A very rare plant in West Wales (or absent if you don’t include Merioneth) but possibly overlooked in a few sites. Small cushions or scattered plants, often reddish and with unawned leaves. Usually fertile with small, shiny, ellipsoidal capsules. Unlikely to be mistaken for any other species except R. sudeticum perhaps but that usually has at least some shortly awned leaves.

Further Notes

Sometimes it’s necessary to verify the genus and then the sinuose cells are fairly reliable:

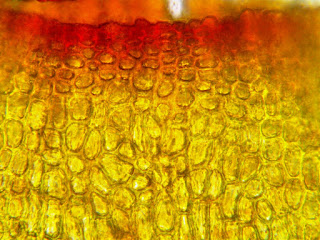

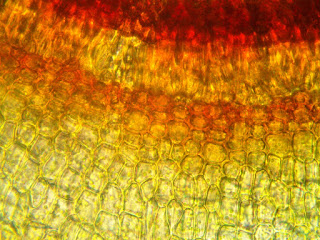

Sinuose cells towards the middle of a leaf of R. fasciculare. Note also the pseudopapillae along the edge of the leaf. In the case of R. fasciculare, the cells frequently almost touch longitudinally, making it look like huge long sinuose cells. There are gaps of course but the cells are still longer than most.

Sinuose cells towards the middle of a leaf of R. fasciculare. Note also the pseudopapillae along the edge of the leaf. In the case of R. fasciculare, the cells frequently almost touch longitudinally, making it look like huge long sinuose cells. There are gaps of course but the cells are still longer than most.

The cells of Racomitrium are not quite unique but only two very uncommon species of Grimmia are likely to cause problems in our area (G. hartmanii and G. ramondii) and are not further considered here, but note that Racomitrium has only one (occasionally two) rows of different cells along the basal margins.

Basal marginal cells of R. sudeticum

It’s often necessary to cut leaf sections to get any degree of certainty. The costa (nerve) is the most useful feature to investigate.

Section of the costa of R. affine in lower half of leaf. At mid leaf there are more usually 3 rows of cells which are quite similar in size, as in the photo. The ventral surface of the costa itself is often flat and the dorsal surface strongly rounded.

The width of the costa is also very useful with R. sudeticum about 60 – 80 microns towards the leaf base, R. affine 80 – 90µ and R. obtusum and R. heterostichum both typically over 100µ.

In determining R. heterostichum the costa really needs to be sectioned but sometimes the broader, flatter costa can be suspected, even with a hand lens.

Costa of R. heterostichum towards the leaf base (above). It is parallel-sided with 3 – 4 rows of cells, clearly differentiated. Further up the leaf the costa remains flat and parallel-sided but generally with 2 rows of cells although then more homogeneous in size (right).

R. fasciculare and R. aquaticum are often identifiable based solely on field characters but some forms of each are more ambiguous and then it is necessary to look for pseudopapillae which they both have. A potential risk of confusion is when R. obtusum (because it is usually muticous too) has what are sometimes called ‘joint thickenings’, again classed as pseudopapillae. These are fairly narrow ridges of tissue running longitudinally which can sometimes be seen edge-on along the leaf margin when viewing a leaf in normal, surface view. Although they might appear to fit the book description of ‘flat-topped papillae’, they are not, as a transverse section can demonstrate:

Pseudopapillae in the cuticle seen along the edge of a leaf in R. obtusum. These thickenings are actually longitudinal ridges with small gaps over cell lumens and quite different from the flat plates of thickened cuticle that cover the leaves of R. fasciculare or R. aquaticum.

Joint thickenings (above, from R. obtusum) and cuticular plates (right) seen in section. The latter are restricted to R. fasciculare and R. aquaticum. This was R. fasciculare.

The leaf apex on R. fasciculare is often very papillose and then there is no ambiguity there as these are clearly not longitudinal ridges:

Leaf apex of R. fasciculare. This is the only place where you actually get an idea of what the cuticular plates look like.

To really see what the cuticle in Racomitrium looks like you need an electron microscope. There are a few pictures available online here

Upper leaf section of R. sudeticum. The V-shape is very clear and is the reason leaves often refuse to lie flat on a slide when a cover-slip is applied.

Separating awned forms of R. obtusum from R. heterostichum

So you’ve got as far as finding a Racomitrium with all leaves clearly awned. You’ve done the leaf section at around mid-leaf and it’s 2 cells thick and parallel-sided. The costa is more than 100µ wide. That’s narrowed it down to R. heterostichum or R. obtusum. This is the list of distinctions that might help but you’ll be extremely lucky if they all fit and it’s likely to need a degree of judgement to arrive at a name. Note that peristome characters are not included because they fail to work on so many occasions.

R. obtusum

Leaf margin broadly recurved and extending well into upper half of leaf, at least on one side.

Costa 4 (-5) cells thick at base.

Awns only occasionally more than 1mm in length (they can be up to about 1.4 mm) and then moderately flexuose when dry. In such cases the long-awned leaves are nearly restricted to the upper parts of the plant and leaves towards the base will only have short awns or may be missing entirely.

Yellowish tinge to plant, at least in upper leaves.

Capsules shortly cylindrical to obovate.

Exothecial cells with rounded corners and generally thick-walled (look about 1/4 way down from mouth).

3 – 6 rows of small, oblate cells below mouth of capsule.

R. heterostichum

Leaf margin narrowly recurved and / or not extending well into upper half of leaf.

Costa 3 (-4) cells thick at base.

Awns often more than 1mm in length (more than 1.5 mm is common) and generally very flexuose when dry. Lower leaves often with awns exceeding 0.5 mm in length so whole pant tends to look hoarywhen dry.

Plants usually mid – to dark-green without a yellowish tinge.

Capsules narrowly cylindrical.

Exothecial cells thin-walled, rectangular.

1 – 3 rows of small, oblate cells below mouth of capsule.

Exothecial cells in R. obtusum (above) and R. heterostichum (right). Thick-walled and quite rounded in R. obtusum; thinner-walled in R. heterostichum. Note also the larger number of rows of small oblate cells below the mouth in R. obtusum.

Conclusion

These are attractive mosses and an important part of the bryophyte flora of acid rock in western Britain and Ireland. It’s going to be more difficult to get secure identifications but well worth the effort. There will undoubtedly be individual patches that are impossible to name by morphology alone however.